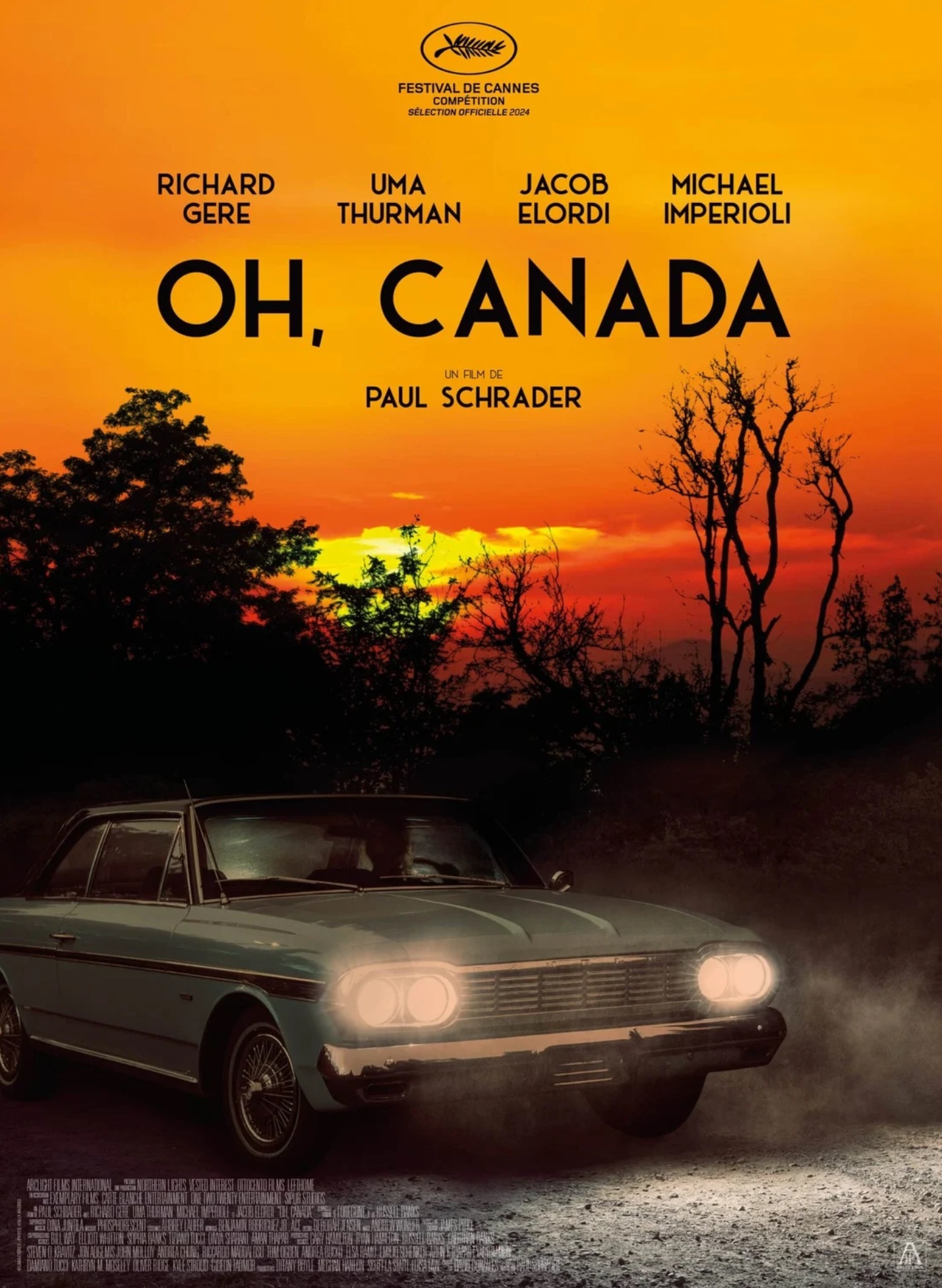

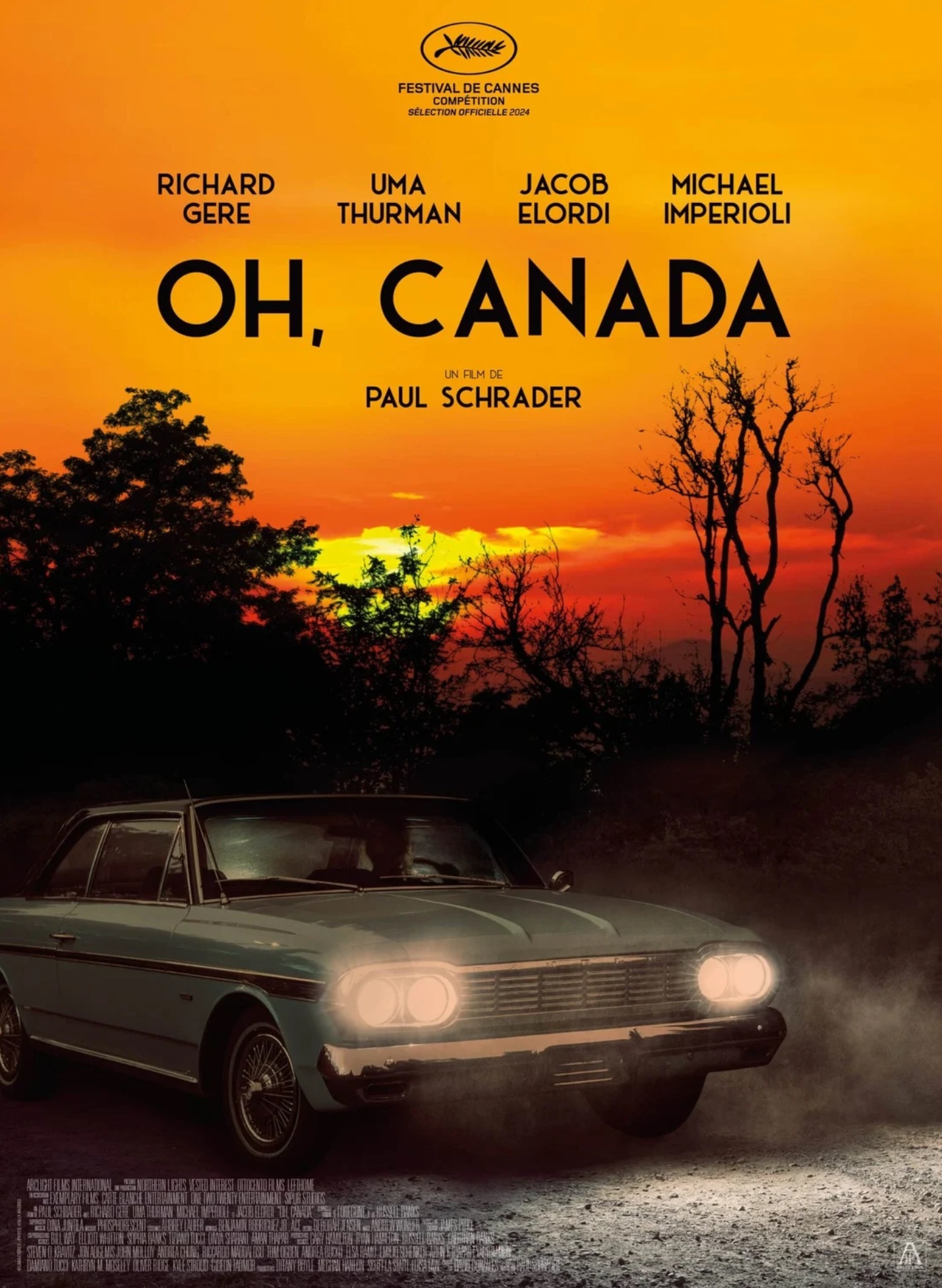

Oh, Canada is a reflective, intimate film that investigates the unreliability of memory using the power of storytelling as a cathartic medium. Through the story of Leonard Fife, played by Richard Gere, a Vietnam War defector who has taken refuge in Canada, Paul Schrader explores how memories resurface in our minds, mingle and shape new remembrances. Are these new memories false? Probably, but they are truthful and genuine for the narrator and, most of all, for the one who chose to listen to them, the viewer, wrapped in the magic of storytelling.

Oh, Canada is a reflective, intimate film that investigates the unreliability of memory using the power of storytelling as a cathartic medium. Through the story of Leonard Fife, played by Richard Gere, a Vietnam War defector who has taken refuge in Canada, Paul Schrader explores how memories resurface in our minds, mingle and shape new remembrances. Are these new memories false? Probably, but they are truthful and genuine for the narrator and, most of all, for the one who chose to listen to them, the viewer, wrapped in the magic of storytelling.

Leonard Fife is a professor, acclaimed documentary filmmaker and symbol of American desertion during the Vietnam War. On his deathbed, he decides to participate in a final film: a documentary-interview about his life. From the first moments of the interview, Leonard establishes the modus operandi: it is his home and he decides what to say. He will be the one to tell his story, refusing any outside intervention. Leonard needs his wife Emma (Uma Thurman) to be there because what he has to say is for her. As soon as the interview begins, he annouces to her and with an on-camera glance at us the viewers, that this will be his testament, his final confession to reveal his infidelity and cowardice. Only in front of the camera is he able to be truthful, to tell the whole truth that he had kept hidden until then. The interview begins with the question of why he left America and fled to Canada, leading him to fame as a model deserter, but having ignored this question Leonard indulges in flights of fancy that will never lead to a clear verbal answer. The film moves forward alternating between past and present, memory and reality, leaving it up to the viewer to decide whether what he is seeing is true or not.

During the course of his interview-monologue, Leonard is repeatedly interrupted by his wife, Emma, who disputes the veracity of the stories he tells. According to Emma, Leonard mixes facts that happened with fictionalized parts, because of his confused mental state due to medication, but also to punish himself for a past he disowns. Leonard calls himself a coward in love and in life having chosen Emma to an idyllic family life and Canada over the Vietnam War. In spite of Emma, lucid and present, his tales are false, yellowed by time to the point of fading. The power of storytelling traps the viewer, turning the falsehood into truth, past into present. This is the power of the word, the narrative power of myth, the power of cinema. By going to the cinema as a spectator, or even simply as an listener of a story being told, we choose to believe the fiction that is presented to us, making ourselves to be enveloped by that imaginary world. Thus contrary to Emma’s warnings, we viewers prefer to believe in Richard’s delusions because we are now enveloped by the power of the narrative.

Oh, Canada, adapted from the novel by Russell Banks Foregone, is however far from being flawless. The dialogues are often vague and difficult to follow, and the main story, which in the first part centers on the lingering question of why Leonard left for Canada, becomes less interessting because of the lack of a clear answer. By the time the explanation is finally provided in the finale, the viewer’s attention has shifted to other details, making the revelation somewhat less impactful.

However, Schrader succeeds perfectly in portraying Leonad’s stream of consciousness, of a person suffering from senility, or at least not completely lucid, using a fragmented narrative that reflects the mind of the protagonist. Delirium places a major part in the stroy being told, the various narratives not fitting together; the same actions switches from Vermont to Canada, from Russia to Florida. It dwells on seemingly insignificant details that sear themself to memory – the muffin at the gas station, fragments of conversations – but at the same time skips important parts. Schrader portrays Leonard in his most delusional state, alternating moments in which he is played by both Richard Gere and Jacob Elordi, and using black-and-white scenes alongside color scenes. Editing is employed as a tool to give fluidity to the story and to respect Leonard’s imagination. The characters in the stories mix and mingle. The people in front of Leonard become those inside his mind, and Emma, his real wife, becomes his imaginary lover. Anyone who has dealt with an elderly relative can understand this feeling of vagueness in the stories about their past, the certainty that the tale being told is a chimera of so many other stories, but also the willingness to keep listening to them. Perhaps this is also why Oh, Canada struck me so much, because it managed to visually display something that until that moment I had only felt inwardly. The power of the film lies precisely in the way Schrader manages to immerse us in this chaotic flow of memories, showing how reality and fiction are inextricably mixed in the protagonist’s mind.

However, Schrader succeeds perfectly in portraying Leonad’s stream of consciousness, of a person suffering from senility, or at least not completely lucid, using a fragmented narrative that reflects the mind of the protagonist. Delirium places a major part in the stroy being told, the various narratives not fitting together; the same actions switches from Vermont to Canada, from Russia to Florida. It dwells on seemingly insignificant details that sear themself to memory – the muffin at the gas station, fragments of conversations – but at the same time skips important parts. Schrader portrays Leonard in his most delusional state, alternating moments in which he is played by both Richard Gere and Jacob Elordi, and using black-and-white scenes alongside color scenes. Editing is employed as a tool to give fluidity to the story and to respect Leonard’s imagination. The characters in the stories mix and mingle. The people in front of Leonard become those inside his mind, and Emma, his real wife, becomes his imaginary lover. Anyone who has dealt with an elderly relative can understand this feeling of vagueness in the stories about their past, the certainty that the tale being told is a chimera of so many other stories, but also the willingness to keep listening to them. Perhaps this is also why Oh, Canada struck me so much, because it managed to visually display something that until that moment I had only felt inwardly. The power of the film lies precisely in the way Schrader manages to immerse us in this chaotic flow of memories, showing how reality and fiction are inextricably mixed in the protagonist’s mind.

As the nostalgic exploration at the heart of the film evolves, Leonard must question the myths underlying his existence realizing that, perhaps, his life has been one big lie, founded on the myth of desertion. Faced with the truth, however, he chooses to embrace the reality of his memory, taking refuge in it, in the power of storytelling.

OH, CANADA

Directed by Paul Schrader

With Richard Gere, Uma Thurman, Jacob Elordi